Chester Lozier, World War I, and the Telegram

By Melissa Jones, Public History Center Fellow, Class of 2018, Christopher Newport University

Editor: Dr. Sheri M. Shuck-Hall, Associate Professor of History, Director of the Public History Center, Christopher Newport University

Chester A. Lozier was an electrician in the United States Navy during World War I and World War II. During WWI, Lozier served aboard vessels that patrolled Mexico, South America, and the West Indies. The majority of the letters in the Chester A. Lozier Manuscript Collection in our Letters Home on this website were written in 1917 and 1918. During this time he served on the Cumberland while it acted as a receiving ship stationed at the Naval Training Station in Norfolk, Virginia. Once in Norfolk and outside the censor on letters, Lozier recounted some of his travels during 1917 to foreign countries when writing to his wife. He went into the most detail about his experiences in South America and the West Indies, specifically when he was in Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and St. Lucia. These letters give a unique glimpse of an American’s perspective on these foreign places during this time period.

Lozier frequently mentioned the use of the wireless telegram in his letters, which gives insight into how technology impacted the war. Telegrams were expensive, but were a faster option to get information to soldiers’ families, such as if they found out they were coming home. The impact of being able to telegram one’s family can be seen in Lozier’s letters. Although they could cause some confusion as letters written before telegrams would arrive after the telegram was received, in general soldiers and sailors utilized this quick means of communication.

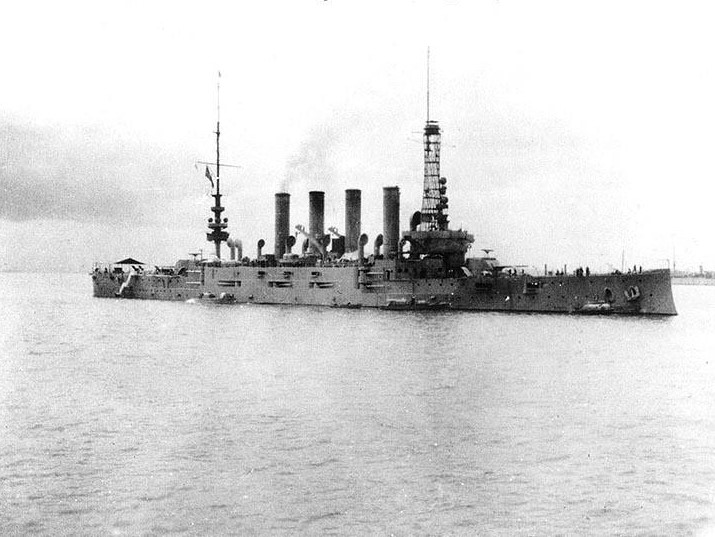

- USS Pittsburgh (Armored Cruiser No. 4) At Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, circa 1917-1918. Lozier served on this ship. Courtesy of Lieutenant Commander Ellis M. Zacharias, USN, 1931. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph #NH 50051. Contributed by USNHC/Fred Weiss

Lozier’s Path of Travel 1917-1918

The United States Navy deployed many ships in 1917 as a part of a defense strategy against German submarine warfare in the Atlantic. Admiral Caperton took four armored cruisers into the Atlantic that year to establish a patrol based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Not only did the United States want a naval presence in the South Atlantic to patrol for German vessels, but officials like Admiral Caperton also were sent there in order to develop and reinforce relations with South American countries. The USS Pittsburgh, which Lozier served on, was one of these patrol vessels in South America whose goal was to stop German and Austrian vessels from entering the East Pacific. In mid-May the Pittsburgh made port at the canal in Balboa, Panama in order to join the Atlantic Fleet. She then continued patrol duty in the South Atlantic, visiting ports in Brazil and blocking German and Austrian ships from sailing from their port in Bahia, Brazil. The Pittsburgh then headed for Montevideo, Uruguay to attend the funeral ceremony of the Uruguayan Minister to the United States, Carlos M. DePena. Following the ceremony, the ship sailed to join the rest of the fleet in South America.

- Stern view of the USS South Dakota (Armored Cruiser No. 9) in dry dock #2, the first ship to dry dock here, at Mare Island on March 15. U.S. Navy Photograph, Contributed by Darryl Baker

Along with other ships in the fleet, the Pittsburgh sailed for the South Atlantic to patrol the seas using ports in Brazil and first docked in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She then anchored at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in August 1917, accompanied by British ships. While the Pittsburgh was docked in Montevideo in November, Lozier was transferred to the USS South Dakota. On her way back to the United States, the South Dakota stopped at a port in St. Lucia to restock supplies. From there she sailed to Hampton Roads, and then Lozier was transported by the tug Hercules to the Norfolk Naval Station.

- The steam tug Hercules, built in 1907. National Park Service Photo

The ships that patrolled the Atlantic and Pacific were very important to the war effort because their job was to stop German and other enemy submarines from shooting torpedoes at naval and civilian ships and to find and block off enemy supply ports. Unrestricted submarine warfare was the main reason that the United States got involved in the war, so stopping enemy submarine attacks, especially on civilian vessels, was a top priority. Although the U.S. Navy did not have many destroyers that were ideal to fight submarines, their naval presence and support of the British fleet had an impact both on the Allies’ morale and pressure placed on the enemy vessels. The Allies’ naval success during the war also was critical to their victory.

One area of naval importance during the war was the Caribbean, which is where Lozier spent a lot of his deployment during WWI. The strategy of the U.S. Navy, as explained by historian Donald Yerxa, was that “fleet units would concentrate at Hampton Roads prior to steaming down to either Guantanamo Bay, Cuba or Culebra, Puerto Rico. From their base in the northwestern Caribbean, scout vessels would fan out to locate the Germans” (Yerxa, 182). This followed the ‘War Plan Black’ that was made in 1913 and 1914, following a 1910 study. The plan outlined that the United States would send fleets to the Atlantic whenever German-American relations became strained, in order to prevent the German capture of bases in the West Indies. This explains why Lozier and much of the United States Navy concentrated much of their time in the Caribbean, especially the West Indies. Another reason that there was a heightened concentrated of naval vessels in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico was because this was the course most vessels took when transporting resources for the war. As Yerxa argues, “to leave such traffic devoid of naval protection in the face of the demonstrated capability of Germany to project submarine warfare to the Western Atlantic would have been unjustifiably risky” (Yerxa, 186).

Once Lozier was back in the United States waiting to be transferred, he recounts some of his experiences from port in the West Indies and South America when writing to his wife. There were a few reasons that United States sailors docked in foreign ports. One was simply for convenience when needing supplies and fuel. Another reason was to show foreigners some of the U.S. Navy’s best ships in order to show the strength of the United States. The Department of State also hoped that the presence of U.S. sailors in foreign ports would help to encourage trade between the two countries, but some naval commanders resented this idea as they viewed their primary job as relating to military affairs and not socio-economic ones.

As Lozier had nothing to do in Norfolk he was very bored and frustrated, but writes that “in Rio [his job] was easier for that is a beautiful place” (Lozier Letters Home Collection, MS0038/01.07#01). He also writes to his wife about a strange scent while crossing the mouth of the Amazon River, which he soon learns is the smell of land. “I had heard of seamen smelling land, but had always taken it with a grain of salt,” he comments (Lozier Letters Home Collection, MS0038/01.10#01). He later writes that the best oranges in the world come from Bahia, Brazil where he thought the city looked like San Francisco.

- Post Card Typographic: Allies Military Parade on the Arsenal- 4 July 1917- Rio de Janeiro. MBC. Lozier would have been in Rio de Janeiro at this date.

Lozier’s most detailed description is about St. Lucia, which is an island that is part of the West Indies. His crew stopped at the island to get coal for their vessel, and Lozier reports:

“the coal was carried aboard in baskets of 115 pounds weight by negro men and women, mostly the latter. They were of all ages, from sixteen to say forty, and carried the baskets on their heads. They were barefoot, and wore skirts to their knees. A dollar a day is about what their average earning was, we were told, though they were paid by the basket, between a cent and a half and two cents, according to the distance carried.” (Lozier Letters Home Collection, MS0038/01.10#01)

He goes on to write that:

“there are very few white people on the island, but all classes of negros…” and “there was a garrison of about 200 Canadian boys on the island, and they were all anxious to get away. It was very hot by day, but cool nights then, and full of malaria they said.” Lozier describes the town by the port as a small edition of Colon. He also comments on the islands in the West Indies writing that “the tropical islands are beautiful, the coloring is so rich, and have to be seen to be appreciated. The tropical fruits are over-rated though, the alligator pears [what we call avocados] being good but the others being rather sickishly sweet.” (Lozier Letters Home Collection, MS0038/01.10#01)

What Lozier revealed in his letters, however, came under scrutiny. Woodrow Wilson’s Espionage Act of 1917 punished anyone who “willfully attempted to obstruct the war effort or who induced others to do so” (Johnson, 45). This affected civilians and the media, but also affected soldiers serving in the United States military. World War I was one of the first times that soldiers were heavily censored in the United States. The Censorship Board was created in October 1917, consisting of the Post Office Department, Departments of the Navy and War, the War Trade Board, and the Committee on Public Information. The board’s job was to regulate telephone calls, radio cable, mail and telegraphs between the United States and foreign countries (“Correspondence”). This censorship extended to mail from sailors abroad.

- Optional Field Service Postcard, a pre-printed card with optional text that could be deleted as appropriate to transmit basic information.

A top priority for censorship was to avoid letting the enemy know where American soldiers were, how many of them were there, and what their strategy was. For this reason many of Lozier’s letters to his wife do not mention where he is or what exactly he is doing. The letters that he writes while deployed contain barely any detail about his experiences, but usually are about how much he misses his family. Only once Lozier returns to the United States and is waiting to be deployed again can he talk about some of the places he visited since he is no longer in foreign territory. Even then he does not mention specific operational details for fear that the enemy will use it to uncover their strategy, but he does write about his experiences in foreign countries. This same obstacle was experienced by many other sailors, who wanted to keep in contact with their families but were not able to tell them any news.

The Telegram and Its Use by Soldiers During War

The telegraph was invented in 1837 by a group of inventors, including Samuel Morse. By 1866 a joint English and American company had successfully laid a transatlantic cable from Newfoundland to Cape Clear, Ireland. This means of communication directly impacted the way news and information spread, especially during wars. The use of the telegraph had even contributed to the Northern victory of the American Civil War. As the technology of the telegraph improved, it became a popular and vital part of spreading news.

- Major telegraph lines in 1891. Telegraph Connections (Telegraphen Verbindungen), 1891 Stielers Hand-Atlas, Plate No. 5, Weltkarte in Mercator projection

Besides official military correspondence, the telegraph could be used by soldiers to wire their families with news, or money could be wired to and from soldiers who were stationed far away. As can be seen from Lozier’s letters, this form of communication was especially helpful with relaying urgent messages, such as letting his family know that he is being transferred or telling them to come visit him while he is awaiting deployment. Letters could take up to months to be delivered to soldiers’ families and friends depending on where they were stationed, so this form of communication was extremely useful for soldiers by allowing for the instant relaying of important messages. In addition to messages, families who relied on the financial support of their deployed loved ones could receive much needed money faster than by letter. Finally, soldiers could use telegraphs to reassure their family members of their well-being, especially after attacks or military engagements in which many soldiers died.

Throughout Lozier’s letters, he mentions several instances of wiring his wife with news, mostly so that she could be aware of where he was. When his ship picked up a wireless before landing in the United States, Lozier wrote to his wife that it made him feel closer to his home and his family. While it was possible for telegrams to cause confusion as they were instantly delivered and older news from letters were received later, overall telegrams helped soldiers stay in better communication with their families while they were away. Telegrams were so important for military communication that men were being taken from other departments and given jobs as wireless men. One of Lozier’s assistant electricians was transferred back to Norfolk because they needed so many men to work the wireless telegraphs (Lozier Letters Home Collection, MS0038/01.16#01).

During World War I, Chester Lozier was able to experience traveling to foreign lands and to benefit from new innovations in technology. His travels through the West Indies, South America, and Mexico allowed him to see how different cultures lived in a variety of countries. He enjoyed the fascinating geography, people, traditions, and food of the lands he visited. Lozier also was able to send quick communication to his family about sudden transfers using telegrams. Because of the telegram, he saw his family frequently while waiting in Norfolk to be deployed again. Luckily, we are able to understand these experiences through Lozier’s perspective because of his collection of letters that has been preserved.

For additional information on Chester Lozier, see his transcripts in Letters Home Collection.

Sources

Andrade, Ernest. “The Battle Cruiser in the United States Navy.” Military Affairs Vol. 44, No. 1 (Feb. 1980) 18-23.

Bektas, Yakup. “Displaying the American Genius: The Electromagnetic Telegraph in the Wider World.” The British Journal for the History of Science Vol. 34, No. 2 (Jun. 2001) 199-232.

“Correspondence.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History. 5 September, 2017.

Healy, David. ”Admiral William B. Caperton and United States Naval Diplomacy in South America, 1917-1919.” Journal of Latin American Studies Vol. 8, No. 2 (Nov. 1976) 297- 323.

Johnson, Donald. “Wilson, Burleson, and Censorship in the First World War.” The Journal of Southern History Vol. 28, No. 1 (Feb. 1962) 46-58.

Marland, E.A. “British and American Contributions to Electrical Communications.” The British Journal for the History of Science Vol. 1, No. 1 (Jun. 1962) 31-48.

Yerxa, Donald A. “The United States Navy in Caribbean Waters during World War I.” Military Affairs Vol. 51, No. 4 (Oct. 1987), 182-187.